On July 11, 2025, the eighth lecture of the 2025 Academic Frontier Lecture Series, titled “Toward the World 30 Years from Now — The Changing Kyōyō, the Changeable Kyōyō,” was held in the Lecture Hall of Building 18 on the Komaba campus. The final session of the lecture was delivered by Professor Ishi Tsuyoshi, under the tiltle “What Is the Integration of the Humanities and Sciences? — Liberal Arts in a Brain-Oriented Society.”

Through an exploration of the etymology of terms such as “art,” “humanities,” and “science,” Professor Ishii reflected on the significance and potential of “liberal arts” in today’s “brain-oriented society.” He pointed out that the name of the university of Tokyo’s “College of Arts and Science” retains the term “arts,” which is absent from the concept of “integrated knowledge” recently promoted by the Japanese government. As a means of representing and giving form to a world full of contingency and uncertainty, the existence of “art” in fact predates “science.” However, in contemporary society, the value of “science” has been excessively inflated, while “art” has been marginalized and dismissed as a surplus within academia.

Professor Ishii traced the historical intersections and divergences between the terms “science” and “art,” examining their evolving relationship. In ancient Greek, the word “art” originates from technē, meaning “technique” or “skill,” highlighting a close and interrelated connection between “art” and “technology.” From this perspective, the concept of the “integration of humanities and sciences” can be seen as rooted in the linguistic traditions of ancient Greece.

Professor Ishii further returned to the East Asian context, tracing the shifts in meaning embedded in the terms bun/gei [文/藝] and ri [理], which have been repeatedly entangled and differentiated throughout history. In the roku gei — “Six arts” [六芸] — the term gei [芸] is understood in a manner similar to the Western concept of “art”, encompassing both technical skill and knowledge. Likewise, in the Shuowen Jiezi [説文解字] — the terms bun [文] and ri [理] share similar connotations, both suggesting ideas such as “patterns” or the underlying textures of the world. With the establishment of the Neo-Confucian thought in the Song dynasty, ri came to be imbued with a new meaning : the “principle that underlies and gives rise to all things,” marking a shift from its earlier semantic scope. Zhu Xi’s interpretation of the phrase kakubutsu chichi — “investigating things to attain knowledge” 格物致知 — further redefined ri as “truth” or “principle” — a view that later served as one of the foundations of modern scientific thought.

In other words, the conceptualization of ri as an autonomous domain equivalent to “natural science,” and the relegation of bun/gei to the status of a mere “residue of science,” is, in fact, a relatively recent development.

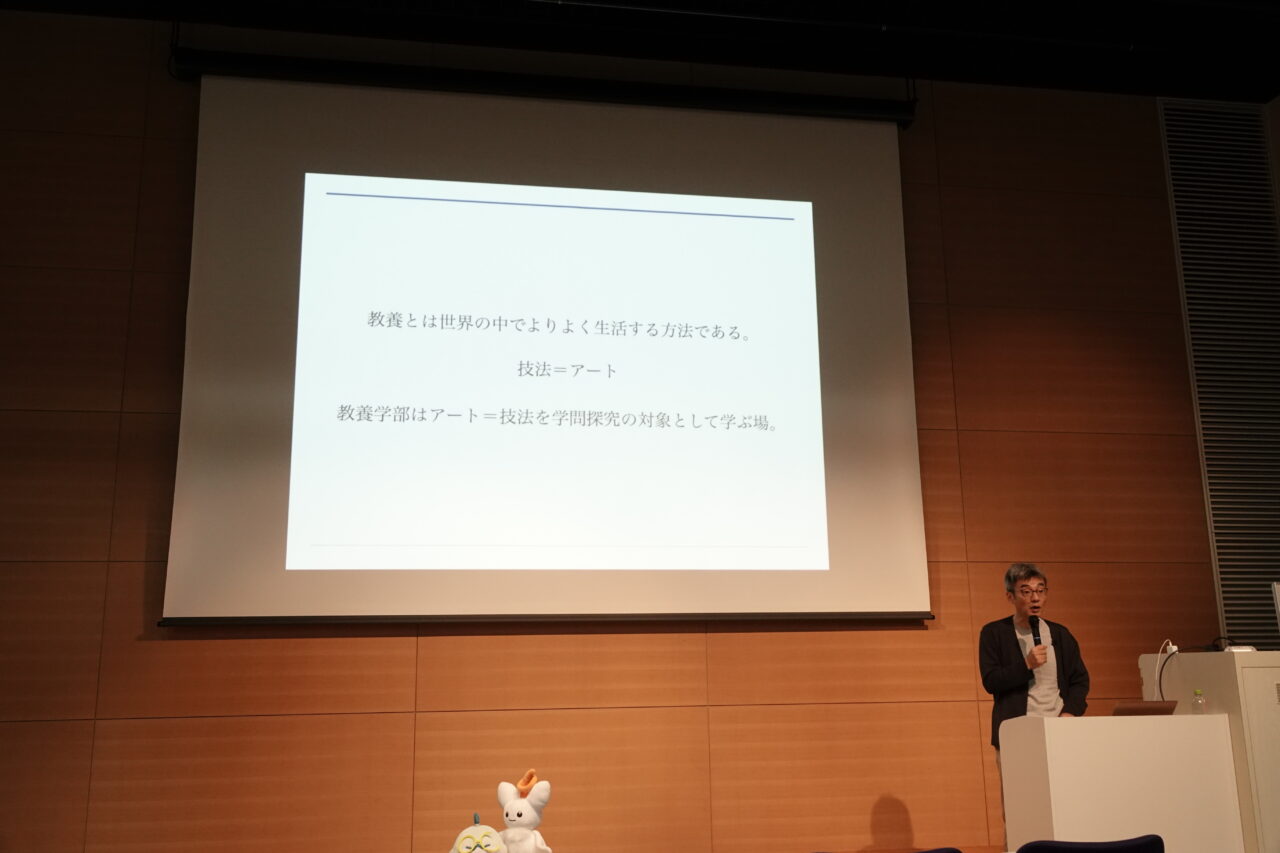

Finally, Professor Ishii highlighted the possibilities opened up by the “College of Arts and Sciences.” As a faculty that retains the term “arts,” it serves as a space where “art” can be pursued as an academic subject. Given that the etymology of “liberal arts” includes the Latin words culture and cultivate, “liberal arts” can be understood as a practical form of tilling and nurturing the world — a technique in the form of art. Thus, the university should not only continue to function as a site of scientific inquiry, but it should also place equal importance on the value and significance of the liberal arts, guiding students to affirm and embrace a world full of contingency and uncertainty.

After the lecture, students engaged in discussions reflecting on the thirteen sessions of the Academic Frontier lecture series held throughout the semester. Topics included the practical possibilities of incorporating “art” into campus life and the relationship between “liberal arts” and happiness.

Writing this report, I am curious to further explore whether the “liberal arts” might offer a means of resisting the growing trends of xenophobia and nationalism in contemporary Japanese society. The rise of xenophobia is deeply intertwined with the political mobilization of emotion: economic and social instability is reframed as a “threat” posted by immigrants and foreigners. By evoking a discourse that protrays the “subject = nation” as being under threat from “the others= immigrants and foreigners,” this rhetoric serves to preserve national stability and unity.

In this context, integrating the “liberal arts” into both education and everyday life may help relativize our fixation on predictability and meritocracy. It may also foster the imaginative capacity to engage with “others” who live under different conditions. In other words, the liberal arts not only help us recognize the fundamental uncertainties that shape our world, but also enable us to understand that immigrants and foreigners grapple with similar forms of instability. In doing so, they open up new possibilities for us to rethink and reimagine the world.

Reporter: Wei, Yun-Dian (EAA Research Assistant)