The webinar ‘Art History Seminar in English’ organised by the EAA on 8 February 2021 attracted over 25 scholars from around the world. This success vividly shows that the EEA is a lively and growing initiative with great potential for evolving into a strong international academic network in the post-Covid-19 era. The event is also the first cooperation between EAA and SiWan College at National Sun Yat-sen University in Taiwan. As noted by coordinators Dr Maeno Seitaro (EAA Assistant Professor), Dr Hanako Takayama (EAA Assistant Professor), and Dr Yusuke Wakazawa (EAA Postdoctoral Fellow) (names listed in alphabetical order), the motion behind holding this event was to provide a virtual platform for interdisciplinary conversation between various fields in arts and humanities, including arts, history, literature, and philosophy, etc. The international context of the event nearly naturally entailed English as the tool for communication.

The idea of choosing Renaissance Art History as the starting point emerged from a conversation between Dr Wakazawa and Dr Koching Chao (Assistant Professor at SiWan College, NSYSU, Taiwan), who is keen to share her research on the socio-political connotation behind Renaissance arts and architecture. Subsequently, Dr Moe Furukawa (Postdoctoral Fellow at Historian Workshop, University of Tokyo) kindly agreed to join this event, and share her studies of one of the greatest sixteenth-century Florentine artists and writers – Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574). The combination of these two talks demonstrates the ways in which visual arts shaping social experience and cultural perception throughout the early modern Italy.

The event commenced with Dr Chao’s talk titled ‘The Hidden Renaissance: Arts or Political Discourse?’, which aimed to draw attention to the invisible aspect of Renaissance masterpieces, that is, their political implications to the contemporary eyes. This approach reflects the new art history trend developed in the 1970s, in which the research scope extends beyond the biographies of individual artists ‘onto social factors, such as artistic, economic, and political. Two cases were selected in order to present a more inclusive view of the ways in which visual arts of religious subject matters were utilised to achieve certain socio-political goals. The first example was the Florentine government’s collection of a series of statues depicting the biblical hero David from the fifteenth century. By positioning these David statues in the contemporary military contexts, Florence’s victory against her fierce opponent Milan in the first half of the fifteenth century seems to reinforce the city’s self-fashioning as the biblical hero, who defeated the dreadful giant Goliath with God’s blessing. In addition, these fifteenth-century Florentine imagery of young David may have served to inspire generations of male citizens to follow the boy warrior’s example to defend their country. The second part of her talk turned to a less known marble relief of Florence’s patron saint, Saint Zenobius, and its metaphorical meaning in relation to the patron family, the Girolami’s. By aligning these two cases of Florentine political life, Dr Chao’s talk shed light on the Renaissance artistic patronage converted into an instrument of political power manifestation in the fifteenth century.

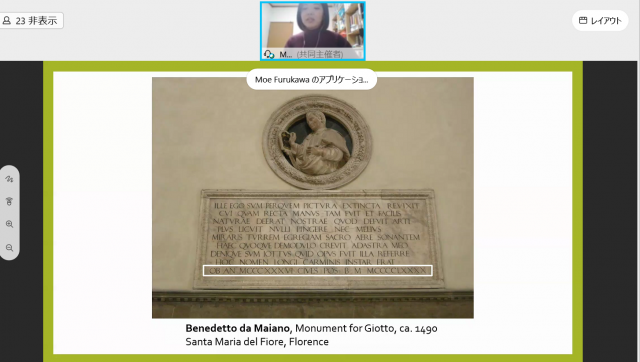

Dr Furukawa’s talk, ‘Commemorating Great Artists in Their Native Land: Tombs and Epitaphs for Artists in 16th-century Florence’ began with two epitaphs commemorating Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael. As Dr Furukawa suggested, this genre of writing not only testified to the contemporaries’ appreciation of the great Renaissance masters, but might also reflect the significance of arts and art patronage for establishing public imagery of individuals. Her investigation indicates that the inclusion of epitaphs in Giorgio Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists was related with his patron’s public imagery: the Medici family. For example, many epitaphs recorded in the second edition of Vasari’s The Lives of the Artists were written by the prominent Florentine humanist Angelo Poliziano, who had a close relationship with Lorenzo de’ Medici (Lorenzo il Magnifico), the de facto ruler of Florence between 1469-1492. Likewise, the mention of Lorenzo de’ Medici’s patronage of a monument for the Florentine artist Filippo Lippi implied his contribution to the heyday of Florentine arts, although historians have confirmed that the actual number of works commissioned by Lorenzo de’ Medici was smaller than what Vasari suggested.

In spite of the different foci of these two talks: one on fifteenth-century sculpture and another on sixteenth-century writings, they shared a mutual interest in the agency of arts, as well as the importance of art patronage in early modern Italian society. After their talks, the speakers and the audience engaged in an extended discussion of the contemporary political circumstances, the relationship between artists, patrons, and viewers, and the literary value of artists’ biographies. As moderator Dr. Takayama summarised, the event was not only about arts, but also about the ways in which arts could evoke intellectual debates and interdisciplinary communication.

Reported by Koching Chao (Si Wan College)