The EAA held the online workshop “Identity, History, and Legal Mobilization: Focusing on Japanese War Orphans from China” on November 24, 2020. The EAA is encouraging young scholars to present their own research and engage in fruitful, constructive, and open exchanges on their research, with the aim of searching for new liberal arts as looking ahead thirty years.

For this event, we were very delighted to have Dr. Hye-Won Um, who recently finished her dissertation and received her Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, as a speaker and Takeshi Shirakawa, Ph.D. student at UH specializing in comparative political philosophy between the West and East Asia, as a discussant. Right before the COVID-19 pandemic began, Um and Shirakawa moved to Seoul and Hawaii respectively, and they have been stuck there ever since. Thus, we met each other through Zoom, connecting three distant places: Hawaii, Seoul, and Tokyo. (The COVID era unintentionally creates academic spaces where people on opposite sides of the world can participate in workshops together despite spatial constraints.)

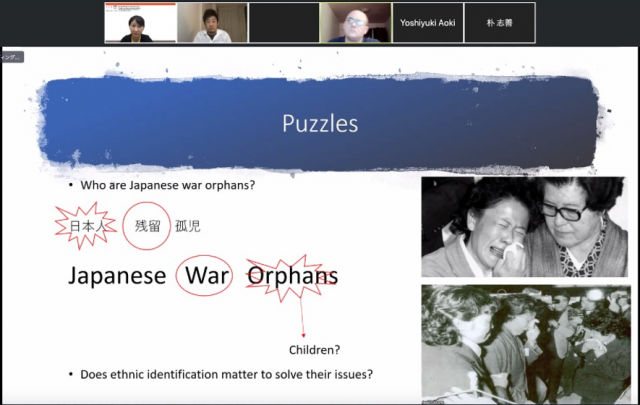

The workshop began with Um’s talk, raising the very sensitive and tangled case of Japanese war orphans. She analyzed why it took more than five decades to resolve the issues around the war orphans’ repatriation and settlement process, exploring the matters of defining Japanese-ness, recognizing state responsibility for civilian damages during the war, and examining peculiarity and universality of the war orphans’ case in the wider context of East Asian history. Debates about the core elements of being Japanese and the war orphans’ desperate struggles for official recognition as Japanese citizens reveal how the boundaries of the Japanese nation have been constantly reshaped through complex and intense negotiations among different social actors. The question “who is the truly Japanese?” is the political battlefield that the issue sheds light on.

Um also pointed out that public ignorance about the wartime history along with governmental reluctance to support the war orphans pushed them to begin legal mobilization as their last resort. The war orphans grew up in China, spoke Chinese, married a Chinese partner, and practiced Chinese customs. Due to their Chinese cultural traits, Japanese public often mistook them as poor Chinese migrant workers. Even when the public found out these Chinese-like people were Japanese, the majority did not understand the war orphans’ unusual situations and the cause for their political struggles. Thus, it was crucial for the war orphans to explain in Japanese courts who they are and why they claimed for the governmental assistance in regard to protecting citizens’ rights. It was also significant that legal recognition of their rights as Japanese citizens can motivate government officials and politicians to formulate new policies on the war orphans.

Despite their desperate activism, they lost all their lawsuits (except for one, a partial winning at Kobe court), as many cases asserting state responsibility for wartime wrongdoings in Japanese courts do. Nonetheless, they were finally able to receive full financial support from the government based on the special package bill under the Abe administration in 2007. It is still not clear why Abe suddenly announced the financial support for the war orphans. However, Um’s analysis seems persuasive. Abe succeeded Koizumi’s legacy on the Japanese victims abducted by North Korea providing them full support package including national pension, national health care, public housing, language education, etc. Abe’s stance on state responsibility for protecting its citizens in the case of these Japanese abductees pressured the government to provide the war orphans similar support package.

Following Um’s talk, Shiraikawa’s discussion penetrates into its relevance with regards to the applicability and comparability; the wavering response of Japanese government, embracing Okinawans and Ainu people as Japanese on the one hand, refusing war orphans as Japanese on the other hand, reflecting that the twisted development of modern nation-state Japan, entangled with territorial expansion schemes.

Participants were also actively engaged in the discussion, raising questions as post-activism after they obtained the so-called “success” in movements, whether they have solidary networks with other relevant cause based civic activism across East Asia, why Japanese war orphans desperately clings to legal mobilization as a movement tactic, and whether the “Japanese-ness” identity in itself has been static or reconstructed, the possibility to see identity as a means rather than a cause or a goal, etc. As you may be aware, to exchange these inquiries back and forth the workshop time was not enough, was much over what we scheduled. It was indeed a thought-stimulating discussion, making us look forward to the next meeting.

Reported by Yoojin Koo (EAA Project Assi. Prof.)