At the inception of film studies as a field of inquiry, the problem of ideology and its representation emerged as one of the central concerns of the field. Yet, our thinking about the problem of ideology vis-à-vis cinema has changed over the past few decades. With the aim of considering this problematic from the vantage point of contemporary Japanese film studies, EAA sponsored an online workshop entitled “Cinema and Ideology”, that was held on June 26th, 2021. The workshop was organized around four video presentations, followed by discussion, and open Q & A.

The broad narrative is more or less familiar: when film studies took shape as a field of scholarly inquiry in the late 1960s, the problem of ideology emerged as one of its central concerns. Moreover, from the beginning of academic film studies, Japanese cinema played an important role, especially for attempts to ‘deprovincialize’ the discourse on cinema. With the recasting of film as an ideological practice, film studies and criticism took upon itself the project of exploring and theorizing film practices that worked to demystify cinematic regimes of seeing and knowing the world.

By the 1990s, earlier lines of inquiry had expanded to include concerns from gender, cultural, and media studies (e.g., the debates on sexual identification, spectatorship, and medium-specificity). Through a process of disaggregation and shifting boundaries (e.g., should the study of film be subsumed under larger fields of inquiry into culture or media?), the problem of ideology tended to be obscured by more immediate questions concerning the topography of film studies as a whole.

While the utility of ideology as a concept has been questioned by some (e.g., Deleuze), others have re-affirmed its central significance for the study of cinema, even as the boundaries of the field remain in motion. Insofar as our thinking about the problem of ideology vis-à-vis cinema has changed over the past few decades, it appeared worth exploring how we might approach this in the present. Which approaches or theories of ideology seem particularly relevant at present?

With this goal in mind, the four presenters each considered it in relation to the study of cinema and media, through readings of specific Japanese films.

First, Phil Kaffen (University of North Carolina at Charlotte) offered a reading of “The Reciprocal Image”, taking as a point of departure the large number of films containing scenes which feature characters staring into the camera (and, by extension, out to the audience). These scenes of “staring back”, Kaffen proposes, orient the image outward, in contrast to the reflexive image, which casts its gaze back at itself. Within film history, such images have generally been either consigned to an object (the face) or to breaking the fourth wall. As Kaffen argues, though, neither of these formulations seem adequate. While speaking to the iconic and multifaceted role the reciprocal image has played in the history of Japanese film, Kaffen’s primary focus is on more its recent manifestations across different media. From here, he proposes that the reciprocity on offer in these images may be said to play a role in our experience of “popular sovereignty” — an experience which remains troubling and worthy of deeper investigation.

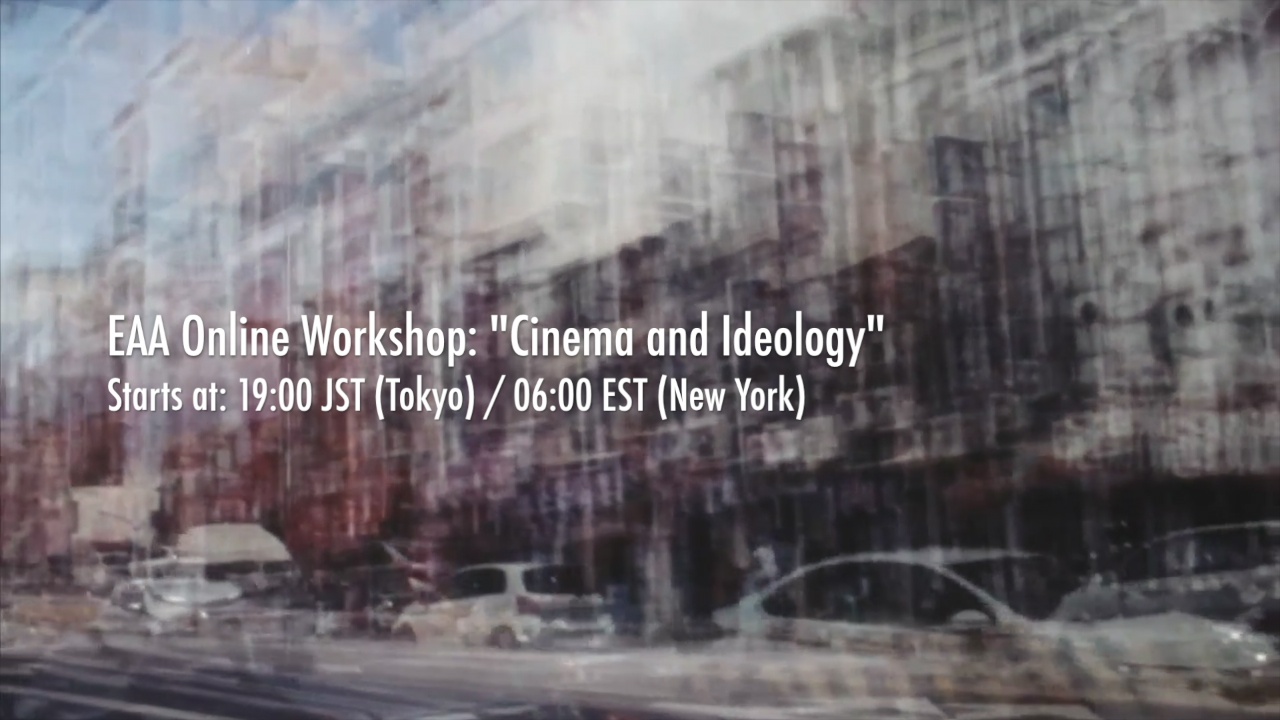

Next, Max Ward (Middlebury College) presented “The Fold within the Frame: Police Power in Japanese Cinema”. Ward begins by noting Thomas Leitch’s observation that Hollywood police films often explore conflicts embodied in their police protagonists (e.g., power vs. justice) which evoke an ambivalence in the audience. The ambivalence appears as spectators negotiate their own antipathy for the police with a common desire for narrative closure, which in turn implies the police as an institution that participates in the reproduction of the social order. Ward argues that the cinematic representation of policing in fact very much resembles the basis on which police power is represented in society, and yet there remains something elusive or indistinct about the place of police power in the socio-political field. As a way to address the question of how cinema takes this indistinct form of power as its object — and what it creates within the sphere of cinema as art — Ward offers an interpretation of Uchida Tomu’s Keisatsukan (1933), in relation to the Ōmori Gang Incident (Ōmori ginkō gyangu jiken) that took place in October, 1932, and Tosaka Jun’s meditations on police power in 1930s Japan. In this fashion, Ward proposes thinking about police power as an “ideological fold”.

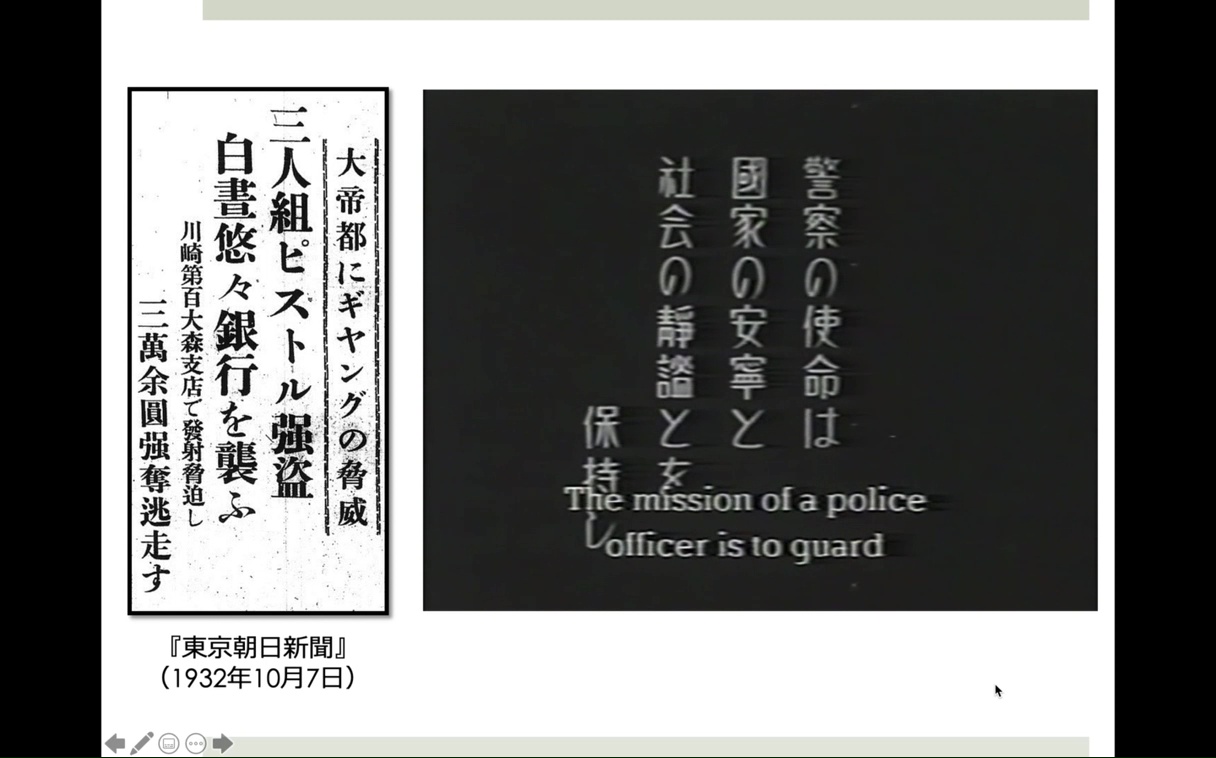

Next, Mitsuyo Wada-Marciano (Kyoto University) presented “Okinawan ‘Mothers’ as Social Thought”, which focused on a reading of Mothers in Okinawa『沖縄の母たち』(1970). For the purposes of reading this film, ideology is proposed as both a conscious line of thought, but also a sensation [kankaku] that a society shares at an unconscious level. Through an analysis of this film, Wada-Marciano argues that Okinawa may be understood as an embodiment of the ‘system of sacrifice’ [gisei no shisutemu] as described by the philosopher Takahashi Tetsuya, which has been concealed in Japanese history. Wada-Marciano proposes to read the Okinawan social structure as it is depicted in this film. More specifically, the analysis explores the sponsorship of the film production, its intended audience, documentary style, and relationship with Okinawan history. Wada-Marciano notes that while the film shows a community of mothers dedicated to a future in which Okinawa is no longer under the shadow of the American Empire and its global network of military bases, what the film doesn’t show the audience is a sense of disappointment or hopelessness felt by mothers, especially, in Okinawa, under its present geopolitical configuration. That is, what the film doesn’t show us is Japan as a suzerain state that, together with the U.S., governs Okinawa as a de facto internal colony.

Finally, M. Downing Roberts (EAA, University of Tokyo), presented “Ideology and Black Mist in Kumai Kei’s Nihon rettō“, in which he offered an interpretation of Kumai’s 1965 film, as well as a recasting of ideological analysis in the wake of the David Rodowick’s critique of political modernism. The reading of Kumai’s Nihon rettō considers its use of remediated, documentary materials, its relationship with postwar reality, and the structure of suspicion that finds expression in the metaphor of “black mist” [kuroi kiri], a term popularized by the writer Matsumoto Seichō around 1960. As a mode of analysis, Roberts proposes parapolitics, not as it has been described by Rancière or Žižek, but rather in line with Peter Dale Scott’s definition of power that is exercised by covert means. Following the argument of Eric Wilson, and as illuminated in Kumai’s film, Roberts considers parapolitical institutions not as fringe or parasitic, but in fact at the center of global governance in the postwar period. In this sense, Kumai’s film may be understood as an ideology critique of the geopolitical condition of postwar Japan, for its protagonists — the journalists, police investigators, public prosecutor, as well as their American military counterparts —, are all shown to be powerless against a parapolitical apparatus.

Reported by M. Downing Roberts (EAA Project Research Fellow)