The second lecture for the EAA Global Lecture Series co-organised by EAA and GGG (Go Global Gateway at the University of Tokyo) was held on 5 October on Zoom. As the second lecturer for the series, Dr. Shuangyu Li (King’s College London) took us through his journey of how he came to his current research question: how doctors communicate with their patients in interpreter-mediated consultations, so to explore how to have more effective, interactional GP consultations that are required in increasingly diverse societies.

According to Li, communication styles in doctor-patient relationships had been dominated by an authoritative and paternalistic relationship, but this has shifted towards patient-centred care in recent years. Previously, doctors were given phrase books that gave guidance of what to tell patients in specific situations. But this attitude has been gradually replaced by ‘healing relationships’, in which GPs value how patients’ feel, and attempt to establish a more equal partnership with them.

What complicates the matter in the UK though, he explained, is a highly diverse population, and this environment seems to have played a vital role in forming his research enquiry and the way in which he engaged with medical education. More than 14 % of the UK’s population consider themselves as non-white. The fact that more than 300 languages are spoken in London alone also shows this diversity (‘Ethnic groups, England and Wales’ and ‘Ethnic groups by English regions and Wales’, Office for National Statistics, 2011). In such culturally and linguistically diverse environment, the component of cultural competence has become an important element in medical education, an element Li incorporates when he develops medical curriculum at his university. The word ‘culture’ that he uses in this context has a broader meaning: it is not just about language, ethnicity, and race but also includes gender, disability, and social and cultural status. But how can doctors communicate effectively while acknowledging the diversity of patients? In the lecture, he shared how the previous studies indicated that an interpreter should be in place to mitigate barriers between doctor and patient when language becomes a barrier. Then how do the doctor, the patient, and the interpreter use language in their interaction to make sense in the interpreter-mediated GP communications?

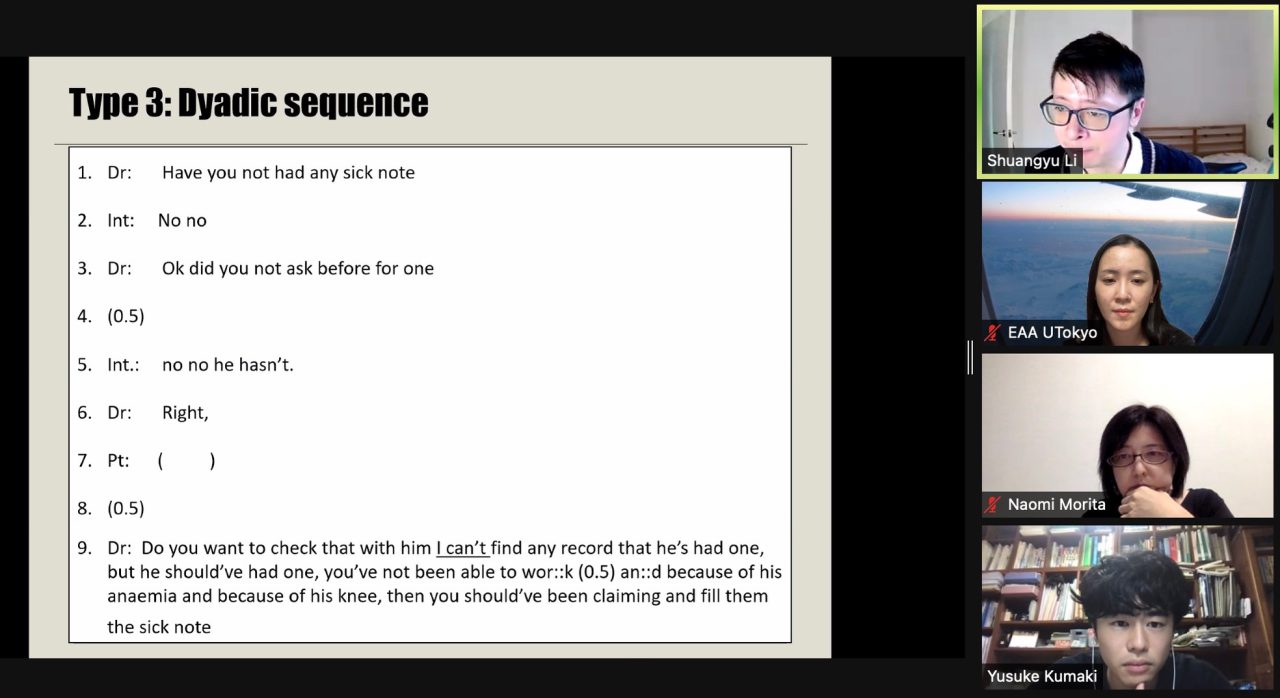

In the rest of the talk, he demonstrated ways in which he used conversation analysis (CA) to explore dynamics at work in such communications. He explained that the way people speak is highly structured and there is a pattern to it; thus, the CA could be an effective tool when analysing and observing patterns of communication (e.g. turn-taking, turn-deign, sequence organisation, social actions). Having explained the methodological aspects of his research, he then shared some results of case studies he conducted. There was much to be learnt from the findings that he shared with us, but one of the results of particular interest was from the case study in which he employed CA. The study is based on the data of seven video recorded GP consultations (with two doctors, seven patients, and three interpreters across levels including professional and ad hoc interpreters of Urdu, Mirpuri, Punjabi, and Czech), in which he identified different types of turn taking and methods of speeches observable in the data (for the detail of his research, see Nine Types of Turn-taking in Interpreter-mediated GP Consultations, Li, S., 27 Feb 2015, In: Applied Linguistics Review. 6, 1). In the lecture, he demonstrated how he analysed the data by reading transcriptions of these interpreter-mediated interactions with particular attention to turns of conversations, pauses, and power dynamics between the doctors, the patients, and the interpreters. This helped us to see how the above-mentioned elements differ between effective and non-effective GP consultations, including the finding that a lot more positive outcomes in the interaction could be expected in cases with longer pauses in the turn-taking, especially when doctors deliver complicated information. To illustrate ways in which one can translate research results into practice, he also showed us how this finding could be used, for instance, to score trainees or to train doctors and interpreters.

The discussion that followed invited us to understand the nature of his research at a more fundamental level. During the discussion, he re-emphasized the importance of being clear about what one would like to find out when one designs research especially for practical purposes – in his case, designing research that would benefit the education of medics. Since most of his audiences work at medical schools, he said, he reduced a lot of technicalities to tailor his research into a more accessible form for those who are not familiar with social science and took a more skills-oriented standardized approach instead of a social science-oriented approach. Having engaged with research motivated by practical purposes to apply its findings to medical education, understanding interactional features that are observable in all consultations even without the language barriers, rather than exploring how to mitigate the linguistic/cultural differences, seems to be the focus of his research. My focus as a literary translation scholar has been the latter, but his lecture helped me revisit the importance of understanding both sides of the spectrum, tasks imposed in increasingly diverse societies, and things to bear in mind when one wants to design research for our future to come.

Reported by Mai Kataoka (EAA Project Research Fellow)